Classic Salmon and Trout Flies

of Europe and the Americas |

|

Biot

Bodies in Depth

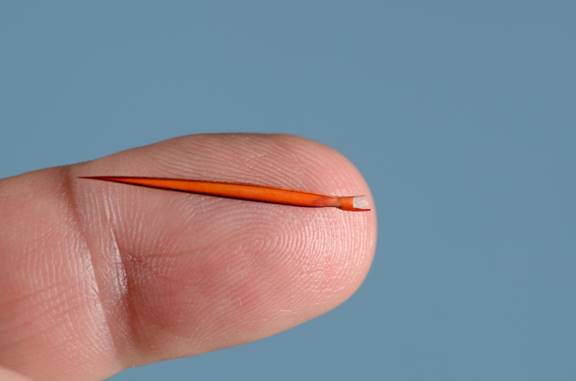

Biots have been used for many

years now to create bodies, tails, wings and antennae for various flies. A

single biot, after the quill has been dyed and one biot stripped from it, looks like this:

Note the "notch" on the right side, in this instance facing

down. This notch is important. If the biot is tied in

by the tip in such a way that when it's wound the notch is trailing, i.e.

facing the bend as it's wound, a smooth body will result. If tied in and then

wound with the notch leading, i.e. notch toward the eye, you'll get a rough

body. The smooth bodies are suitable for duns and spinners, the rough bodies

for emergers and cripples. There are some emergers done with smooth bodies, notably

Brooks Sprout and René Harrop's CDC Biot March Brown Emerger.

Simple enough and this has been the doctrine taught for

years and fine as far as it goes. However, several years ago I began to notice

some things. Sometimes, when winding a smooth body, I found I was winding with

the general curvature of the biot, but other times I

wasn't, and that seemed to result in a body that was difficult to finish off,

and had something of a lump at the tie off point. What was going on?

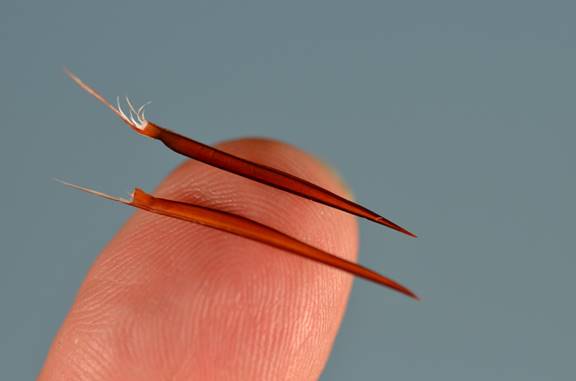

Consider these photos. Here are two biots,

facing convex side up on my finger. One has the notch up, the other down. It's

surprising that the notches don't both point the same way.

The notches point opposite each other because the top one is

from a left goose biot quill, the one on the bottom is

from a right goose biot quill.

Here are left and right goose primary feathers that have

been dyed rusty brown. The quill I'm calling the "left" is on the left side of

this picture:

The biot section on these feathers

is the leading edge, i.e. the smaller side of the rachis or stem of the

feather. The other side of the feather, the wider one, is decidedly not the biot side, though these strands can be used for bodies at

times too (see the Pre-Hatch Baetis recipe). Here's a

close-up, and you can see where I've harvested some biots

for use in this article:

Biots harvested from the left

feather will, when wound with the natural curvature of the biot

(concave side toward the hook shank), result in a smooth body. Biots harvested from the right feather and wound with the

natural curvature of the biot will result in a rough

body. But why is it necessary to wind with the natural curvature of the biot? It's not absolutely necessary, but it is easier to

tie off and results in a better shape, especially when winding smooth bodies.

Consider the following photos:

The first shows a left biot tied

in on the far side of the hook with the convex side toward the hook. I tie many

other materials, ribbing, silk, etc. in this way. It's a very clean way to

begin winding, the first turn starting under the hook When wound, the concave

side of the biot the will be against the hook. This

means we'll be winding with the natural curve of the biot.

The biot will wind with the notch trailing. The next

picture shows the result after the biot has been

wound, a smooth body:

The next photo shows a right biot

tied in with the convex side toward the hook again, and this time the notch is

up. Tied in this way we will wind with the natural curvature of the feather

again. When this biot is wound, the result will be a

rough body, as the biot will wind with the notch

facing forward:

Next we'll wind a right biot but

this time tie it in with the concave side toward the hook, so that when wound

the convex side will be against the hook, winding against the natural

tendencies of the biot. You'll still get a smooth

body if you start with the notch down, but it will be much more difficult to

tie down, and it will result in a bit of a lump, visible in the shot of the

completed body:

The long and the short of all of this is the following: If

you want to wind with the natural curvature of the biot,

and I'm convinced it's a better way, and you want a smooth body, wind a biot from the left quill. If you want to wind with the

natural curvature of the biot, and you want a rough

body, use a biot from the right quill. Tie either one

in so the concave side will face the hook shank when wound, and you're life

will be so much easier.

I sort all of my biots into rights

and lefts now, even if they come as strips alone. To identify whether or not a

strip is from a right or a left quill, simply pull off a biot

and hold it horizontally against the tip of your finger, notch to the left, convex

or shiny side up. If it's a left, the notch will be down. If it's a right, the

notch will be up. Once you've sorted your biot strips,

tie them all in the same way, and use the lefts for smooth bodies and the

rights for rough ones. Does this apply to turkey biots

as well? It applies to all biots, regardless of the

bird.

I prefer goose biots to turkey biots as the segmentation is more distinct. That said,

sometimes a goose biot is not long enough. You may

use turkey then, or perhaps dye a quill from some other larger bird.

For years I wondered where René Harrop

found biots with such a distinct black edge. His

spinners almost looked as if he had run a black thread along the edge of the biot. The secret is Canada goose. The markings on those biots are very black. There is at least one material

supplier now dying Canada goose biot quills, but if

you know a hunter, you can dye your own. You'll need to factor in the naturally

gray color of the biot when dying. To get a PMD

color, use Jaquard Yellow Sun, to get a Rusty color, Jaquard Burnt Orange works well.

Rusty Spinner Step By Step

Step 1.

Create a split tail with what ever

method makes you happy. Here's how I do it. Wind thread to the bend. Leave a long

tag end of thread hanging off the back. Create a small thread ball at the rear

and then spiral thread forward to about the 1/3 position on the shank.

Step 2.

Measure 6-8 hackle fibers or 4 microfibbets

to full hook length. Tie them in and wind thread halfway back to the tail to

secure them.

Step 3.

Pull the thread tag forward, splitting the tail fibers

evenly. Tie the thread tag down on your side of the hook under tension. This will

lock in the near tail fibers. Hold the far tail fibers in place and wind back just

to the thread ball. The tails should be hook length or even longer on a

spinner.

Step 4.

Trim the hackle butts and thread tag. Take the thread all

the way forward to the eye, then back to about the 1/3 point on the shank. On a

#18 hook this is 6 or 7 turns.

Step 5.

Take 2 light dun CDC feathers and hold them back to back so

the tips splay out. Measure them against the hook shank. We want them to be

about hook length when tied in.

Step 6.

Tie them in vertically on top of the hook. Bind down with 4

or 5 wraps back toward the bend.

Step 7.

Cut the butts off at an angle, and bind down all the way to

the tail. Try to create a tapered underbody. Tie in a biot

from a left biot quill by the tip on the far side of

the hook. Tie it in so the convex side is toward the hook shank. The notch

should be down. If it's not, you have a biot from a

right quill, or you have the concave side toward the shank.

Step 8.

Wind the biot forward using hackle

pliers and tie off.

Step 9.

Post the wings up by holding them vertically with the left

hand and making 10 or more wraps in front of them. Be sure to wind down to the

eye every so often, and back up, to make a gradual taper.

Step 10.

Separate the wings out into the two original CDC feathers,

by pinching and forcibly moving the wings into a spent position. Hold the near

wing in place with the left hand and take 4 diagonal wraps, front to back,

moving up the wing. Try not to affect the far wing at all as you do this.

Step 11.

Here is a top view

close-up, showing the diagonal wraps across the near wing in the center. These

will help keep the wing in place. Take one wrap behind the wings.

Step 12.

Now take 4 diagonal wraps back to front, while holding the

far wing in place. Try not to affect the near wing. This should be the result:

Step 13.

Place a number of thread wraps right in front of the wings

while holding them back on top of the shank as shown. Then let go and take a number

of wraps right behind the wings. We want to secure these with thread wraps, not

rely on dubbing to do it later.

Step 14.

Position the thread at the rear of the thorax, and then

begin to dub forward. When you get in front of the wings, duplicate the same

diagonal thread wraps you did previously only this time with dubbed thread. You

may only need a couple of diagonal wraps each direction. The thorax should be

rather robust, but be careful to not crowd the eye with dubbing. Whip finish at

the eye. The wings should angle up just slightly, 10 degrees or so. That makes

this fly very easy to spot on the water

Step 15.

Here's what the fly should look like from the top.

The Last Chance Cripple Step by Step

Step 1.

Start the thread just in back of the eye and wind back to

the bend. Tie in 3 well marked wood duck flank feathers to create a tail that's

about ¾ the length of the hook shank. Take the thread forward to the midpoint

of the shank.

Step 2.

Tie in a piece of rusty dubbing that has been formed into a

noodle by spinning between the thumb and middle finger.

Step 3.

Fold the dubbing back over itself and wind thread to the

bend. Cut the dubbing roughly to create a shuck.

Step 4.

Tie in a right biot on the far

side of the hook, convex side against the hook. Take the thread up to the 1/3

point on the shank.

Step 5.

Wind the biot forward with hackle

pliers to the halfway point of the shank and tie off. Be sure not to go any

more than halfway, space is at a premium from here on.

Step 6.

Finely dub a long piece of thread with PMD dubbing and then

wind an egg shaped thorax. Try to confine it to the 2nd quadrant of

the shank, leaving the first ¼ of the shank for the wing and hackle.

Step 7.

Hold two pieces of light dun CDC between the thumb and

middle finger of the left hand, back to back, tips forward and splayed out. Tie

them directly on top of the hook with a pinch wrap and then take 4 wraps back

toward the dubbing ball, securing the wing on top of the hook.

Step 8.

Clip the butt ends straight up and down at the end of the

thorax, as shown.

Step 9.

Tie in a piece of PMD dyed hackle one size smaller than the

hook. This hook is an 18, so I've used a #20 hackle. Wind the hackle forward

and trap it by taking a wrap behind it as you hold it up, then in front of it,

then behind it again.

Step 10.

Take one wrap in front of the wings at the eye, then one

behind the wings, then whip finish just behind the eye, in front of the wings.

Cut the thread.

Step 11.

Finally, trim the hackle stem carefully. Find the stem with

the slightly opened tips of your scissors and cut it. You're done!

Background image from "Trout" by Bergman (1938)